Did you know that a significant number of material failures in high-temperature applications are attributed to a phenomenon known as creep? Creep refers to the slow, progressive deformation of a material under persistent mechanical stresses, even when these stresses are below the material’s yield strength.

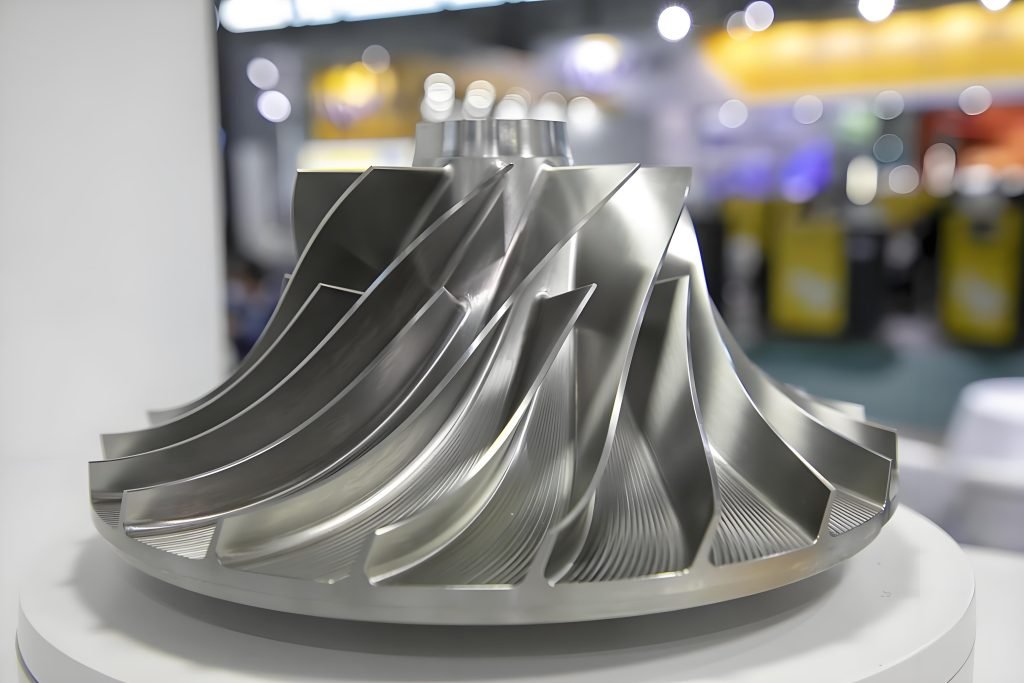

This time-dependent deformation can lead to permanent damage and eventual failure of the material. Creep is particularly relevant in industries where materials are subjected to high temperatures and sustained loads, such as in turbine blades and pressure vessels.

Understanding creep is crucial for engineers and designers to predict and prevent material failure. By grasping the mechanisms behind creep, you can make informed decisions in material selection and design processes.

What is Creep in Materials?

Creep is defined as the time-dependent deformation of materials under constant stress, particularly when the stress is below the material’s yield strength but maintained over extended periods. The rate of deformation is influenced by the material’s properties, exposure time, temperature, and the applied structural load. For instance, materials like lead can creep at room temperature, while others like tungsten require much higher temperatures.

The basic mechanism of creep involves the gradual movement of atoms or dislocations within the material’s structure, leading to permanent changes in shape without immediate failure. Creep deformation generally becomes significant at temperatures near a material’s melting point, typically above 35% of the melting point (in Kelvin) for metals and 45% for ceramics.

Importance in Engineering and Design

Engineers must consider creep when designing components for long-term use, especially in applications where dimensional stability is critical or where components operate at elevated temperatures. The importance of accounting for creep in engineering design cannot be overstated, as it affects a wide range of applications, from power generation equipment and aerospace components to everyday plastic products and building materials.

Understanding creep is essential for predicting the lifespan and performance of materials under constant stress. By acknowledging the factors that influence creep, such as temperature and material properties, engineers can develop more robust and reliable designs.

The Three Stages of Creep Deformation

Understanding the three stages of creep deformation is essential for predicting the long-term performance of materials in various engineering applications. Creep deformation occurs when materials are subjected to constant stress over time, leading to a gradual deformation that can eventually result in failure.

Primary (Transient) Creep

During the primary or transient creep stage, the strain rate is initially high but gradually decreases as the material’s internal structure adjusts to the applied stress. This adjustment occurs through mechanisms such as work hardening, where the material becomes stronger as it deforms. The strain rate in this stage is a function of time, and in materials classified as Class M (which includes most pure materials), the primary strain rate decreases over time.

Secondary (Steady-State) Creep

The secondary or steady-state creep stage represents the longest period in most creep processes. Here, the strain rate reaches a relatively constant value as competing hardening and recovery processes achieve a balance. The dislocation structure and grain size reach equilibrium, resulting in a constant strain rate. Equations that yield a strain rate typically refer to the steady-state strain rate, making this stage crucial for understanding the long-term behavior of materials under stress.

Tertiary Creep and Failure

In the tertiary stage of creep, the strain rate exponentially increases with stress, leading to eventual failure. This acceleration is often caused by the formation of internal voids, cracks, or necking, which concentrate stress in smaller cross-sectional areas. As a result, the true stress on the material increases, further accelerating deformation and ultimately leading to fracture. Understanding the tertiary stage is critical for predicting the point of failure and designing safety factors into engineering components.

Mechanisms of Creep in Materials

The deformation of materials under constant stress, known as creep, is governed by several key mechanisms that are critical to understand for engineering applications. Creep deformation occurs through several distinct mechanisms, each dominating under specific combinations of temperature, stress, and material microstructure.

Diffusional Creep Mechanisms

Diffusional creep mechanisms involve the movement of atoms through the crystal lattice or along grain boundaries. These mechanisms are significant at high temperatures and low stresses.

Nabarro-Herring Creep

Nabarro-Herring creep involves the diffusion of atoms through the crystal lattice. Atoms diffuse from areas under compression to areas under tension, causing the grains to elongate in the direction of applied stress.

Coble Creep

Coble creep operates similarly to Nabarro-Herring creep but involves atoms diffusing along grain boundaries rather than through the crystal lattice. This makes Coble creep more prevalent in fine-grained materials where the grain boundary area is larger.

Dislocation Creep

Dislocation creep involves the movement of line defects (dislocations) through the material’s structure. This movement is often facilitated by both glide along slip planes and climb processes that allow dislocations to overcome obstacles. Dislocation creep is dominant at high temperatures and high stresses.

Grain Boundary Sliding

Grain boundary sliding becomes important at high temperatures, where adjacent grains can move relative to each other. This movement contributes significantly to the overall creep deformation, especially in materials with a small grain size.

Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for predicting and preventing creep deformation in materials used in various engineering applications. By knowing how different conditions affect creep, engineers can design materials and structures that are more resistant to creep deformation.

Factors Affecting Creep Behavior

Creep behavior in materials is affected by a combination of factors, including temperature, stress, and material properties. Understanding these factors is crucial for predicting how a material will perform under constant stress over time.

Temperature Effects

Temperature is a critical factor in creep behavior. As temperatures approach 35-45% of a material’s melting point (in Kelvin), creep rates significantly increase. For metals, this typically occurs at around 35% of their melting point, while for ceramics, it’s at about 45%. Creep deformation becomes more pronounced as the material’s temperature nears its melting point.

Stress Dependency

The stress applied to a material also plays a significant role in its creep behavior. Different creep mechanisms exhibit different stress dependencies. For instance, dislocation creep often follows a power-law relationship, whereas diffusional creep typically shows a linear relationship. Understanding these stress dependencies is essential for predicting how a material will behave under various loads.

Material Microstructure and Properties

A material’s microstructure is vital in determining its creep resistance. Factors such as grain size, grain boundary structure, and the distribution of precipitates can significantly affect how quickly a material deforms under constant stress. The presence of alloying elements or impurities can also alter creep behavior by affecting dislocation movement, diffusion rates, or grain boundary properties.

By understanding these factors, engineers can develop materials with enhanced creep resistance by optimizing their composition and processing to create microstructures that resist the specific creep mechanisms active under the intended service conditions.

Common Examples of Creep in Everyday Applications

As you go about your daily life, creep is likely occurring in various materials and products around you. Creep manifests in numerous everyday applications, from industrial equipment operating at high temperatures to common household items that gradually deform over time.

Industrial Applications

In industrial settings, you’ll observe creep in power plant components like turbine blades and boiler tubes, where metals operate continuously at high temperatures under significant mechanical loads. Structural steel in buildings and bridges can also experience creep over decades, particularly in regions with high ambient temperatures or in components exposed to heat sources. This can lead to a gradual deformation of the metal parts, potentially resulting in creep failure.

Household and Consumer Products

Household and consumer products frequently exhibit creep failure, especially plastic components under constant load. Examples include sagging shelves, deformed plastic containers, or failed plumbing fittings. Even at room temperature, soft metals like lead and solder can creep under relatively light loads, explaining why lead roof flashings gradually deform and why electronic solder joints can fail over time despite being well below their melting point.

For instance, a homeowner discovered water pouring down their driveway due to a fractured plastic threaded connector that had undergone creep deformation over 12 years. This example highlights the importance of understanding creep behavior in materials to prevent such failures in various applications.

Measuring and Testing Creep Resistance

To evaluate a material’s creep resistance, engineers employ specific testing protocols that simulate long-term material behavior under constant stress and elevated temperatures. This process is crucial for understanding how materials will perform over time in various applications.

Standard Creep Testing Methods

Standard creep testing involves applying a constant load to a specimen maintained at a controlled temperature, with precise measurements of strain recorded over extended periods. Creep tests typically produce data in the form of creep strain versus time curves, which engineers analyze to identify the three stages of creep and determine critical parameters like minimum creep rate. These tests can last weeks or months, providing valuable insights into a material’s creep behavior.

Interpreting Creep Test Results

Interpreting creep test results involves extracting key parameters such as the stress exponent and activation energy, which provide insights into the dominant creep mechanisms and help predict long-term behavior. Advanced testing techniques may include multiaxial stress states, variable temperature conditions, or accelerated testing protocols that help engineers develop reliable models for predicting component lifetimes under creep conditions. By analyzing these results, engineers can better understand how to minimize creep deformation in various applications.

Preventing and Minimizing Creep Deformation

By adopting the right materials and design strategies, you can significantly reduce the risk of creep deformation in your applications. Creep deformation can be minimized through various approaches, including selecting materials with higher melting points for high-temperature applications and using materials with larger grain sizes to reduce grain boundary diffusion.

For high-temperature applications, specialized creep-resistant alloys containing elements that form stable precipitates or solid solutions can dramatically improve performance. Microstructural engineering offers another approach to minimizing creep, where controlled heat treatments can optimize grain size and precipitate distribution.

Design strategies to reduce creep include lowering operating stresses by increasing cross-sectional areas or adding support structures. Operating equipment at lower temperatures whenever possible provides one of the most effective ways to reduce creep, as even small reductions in temperature can significantly extend component life.

Regular inspection and monitoring of components susceptible to creep can help identify early signs of deformation before catastrophic failure occurs. In some applications, periodic heat treatments or stress-relief procedures can help reset the microstructure and extend the useful life of components operating in creep conditions.

FAQ

What is the primary cause of creep deformation?

Creep deformation occurs due to prolonged exposure to high temperatures and stress, causing permanent deformation over time.

How does temperature affect creep behavior?

Temperature plays a significant role in creep behavior, as high temperatures increase the rate of deformation and can lead to a reduction in the material’s melting point.

What is the difference between diffusional creep and dislocation creep?

Diffusional creep involves the movement of atoms within the crystal lattice, while dislocation creep occurs due to the movement of dislocations, resulting in plastic deformation.

How can creep deformation be minimized or prevented?

Creep deformation can be minimized by selecting materials with high creep resistance, controlling operating temperatures, and reducing stress levels.

What are some common examples of creep in everyday applications?

Creep can be observed in various industrial and household applications, such as high-temperature equipment, turbine blades, and structural components.