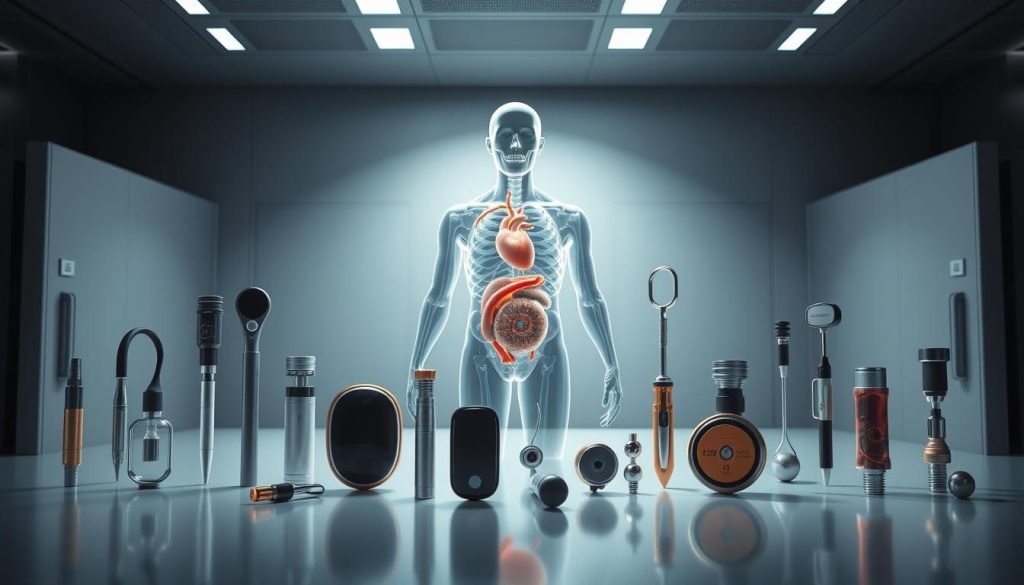

Fast demand and innovation of the implantable medical devices market are rising. You’ll get a practical roadmap that explains what these devices are, how they support the human body, and why growth is accelerating now. Advances in technology, an aging population, and new FDA paths are expanding options for patients and manufacturers alike.

This guide outlines main types and real-world examples like pacemakers, ICDs, and LVADs, and it clarifies differences between active and passive implants. You’ll also see how materials — metals, polymers, ceramics, and biologics — are chosen for strength and biocompatibility.

Finally, you’ll learn the basics of manufacturing, key regulatory expectations, and where Fecision’s services can help you move from concept to compliant production.

Medical Device Implants

Devices placed inside the body restore function, monitor conditions, or deliver therapy to improve patient outcomes.

What they are and how they help

An implantable device is introduced during surgery or a clinical procedure to serve a specific role. You rely on these systems to restore mobility, enable long-term drug delivery, or measure physiology remotely.

Active vs. inactive implantable devices

Inactive implants are passive—orthopedic hardware, IUDs, and ports that provide structural or contraceptive control. Active implantable medical devices use stored power or external energy to sense, stimulate, or pump, such as pacemakers and LVADs.

Market momentum and typical examples

Demand in the United States grows with aging populations, chronic conditions, and limited donor organs. Typical examples include artificial joints, vascular access systems for chemotherapy, contraceptive IUDs, and neurostimulators for pain or movement disorders.

Cardiac and beyond

Cardiac systems you should know are pacemaker units, implantable cardioverter shock systems, and left ventricular assist pumps. Beyond the heart, expect neurostimulators, implantable drug delivery systems, and biosensors that support remote care for people managing complex conditions.

Types of Implantable Medical Devices

Understanding how different implant types work helps you match design, testing, and clinical needs.

Active implantables: cardiac stimulators and assist devices

Active implants use power and electronics to treat or support the heart. Examples include pacemaker systems, ICDs, and left ventricular assist devices that support circulation.

Surgical placement, hermetic packaging, and battery life are critical design drivers for these devices.

Passive prosthetics and structural implants

Passive types restore form and load-bearing function without onboard power. Artificial joints and structural prostheses rely on bone integration and durable materials.

Surgical fixation and wear resistance shape material selection and long-term performance goals.

Diagnostic, monitoring, drug-delivery, and vascular access

Monitoring implants capture continuous data for life-critical conditions and guide therapy decisions. Drug-delivery implants and implanted vascular ports support treatment in hospitals and at home.

Each type has distinct constraints on size, biocompatibility, and infection control that affect your development path.

Typical Examples of Medical Device Implants

Real-world implants illustrate the engineering and clinical trade-offs you’ll face. Below are concrete examples across cardiac rhythm management, circulatory support, and non-cardiac implants to guide your design and validation choices.

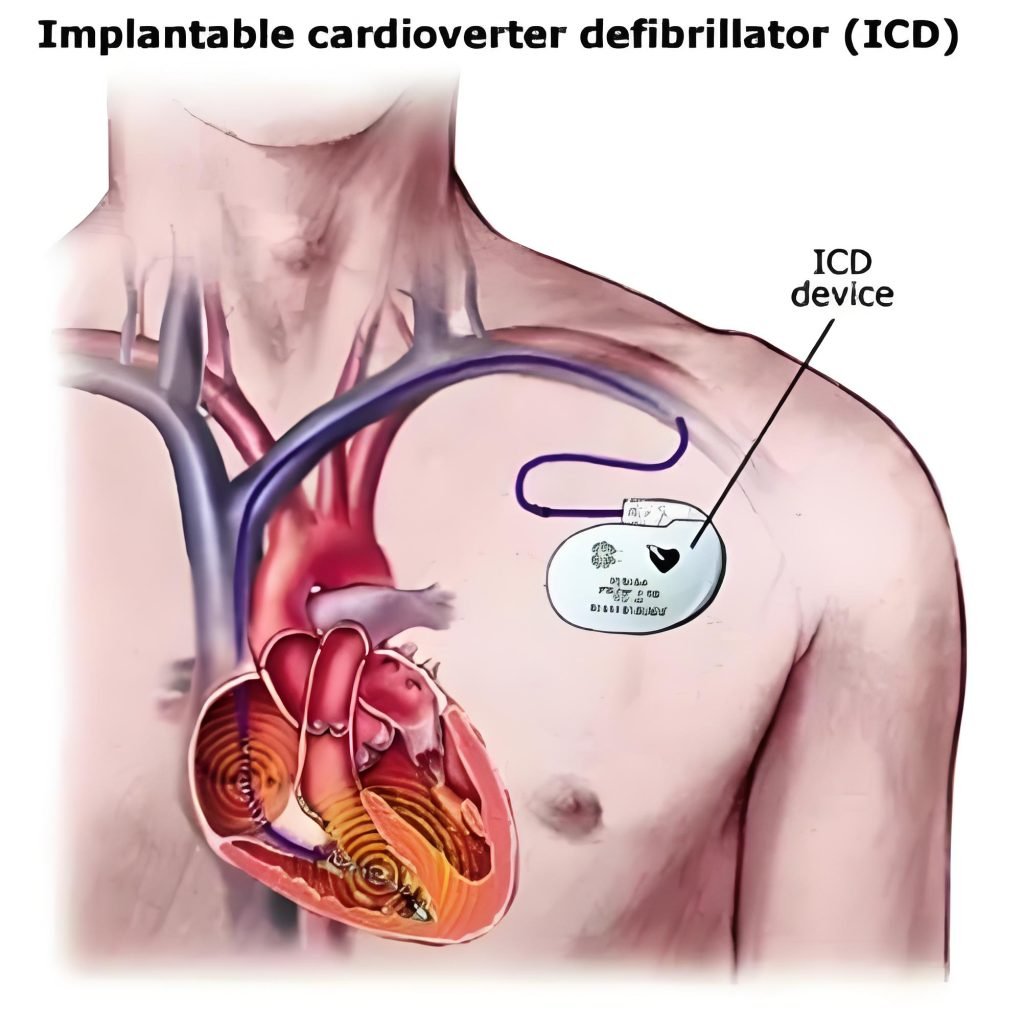

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD)

An ICD is a small, battery-powered device placed under the skin that senses abnormal rhythm and delivers shocks for sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. It prevents sudden cardiac death and drives tight requirements for sensing accuracy, lead reliability, and power longevity.

Pacemakers

A pacemaker uses leads in heart tissue to send timed impulses that maintain rhythm and rate. Temporary systems may support recovery after a heart attack, while long-term pacemakers demand durable batteries, secure lead fixation, and clear telemetry for follow-up.

Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD)

An lvad is a surgically implanted pump that moves blood from the left ventricular chamber to the aorta. It can be a bridge-to-transplant or destination therapy and requires portable controllers, alarms, and robust power systems so patients can live at home.

Beyond the heart

Other common implants include artificial joints, intrauterine devices, cochlear systems, and intraocular lenses. These examples show varied geometries, fixation strategies, and material needs that affect sterilization, packaging, and long-term reliability.

Common Materials for Implantable Medical Devices

Your choice of metals, polymers, ceramics, or biologic materials determines how a device performs and how the body reacts over time.

Metals and alloys for strength and biocompatibility

Titanium, cobalt‑chromium, and stainless steel are the go‑to metals for load-bearing parts like orthopedic joints and cardiac supports. They offer strength, corrosion resistance, and a long history of safe use in the human body.

Polymers and elastomers for flexibility and tissue integration

Polymers such as PEEK and UHMWPE provide wear resistance for articulating pairs. Silicone and ePTFE add soft interfaces that help tissue heal and comply with motion around a device.

Ceramics, composites, and biologics for specialized performance

Ceramics like alumina or zirconia give low friction on joint surfaces and high wear life. Composites and biologic grafts can promote osseointegration or hemocompatibility where needed.

Surface treatments—anodization, passivation, coatings—improve biocompatibility and manage host response. Testing (cytotoxicity, sensitization, long‑term degradation) and manufacturability tradeoffs must link to your quality plan early.

Medical Device Implants Processing Methods

Manufacturing processes turn complex concepts into parts that meet strict clinical and regulatory needs. This section shows core fabrication routes, electronics integration, finishing, and quality steps you’ll need during development of implantable medical devices.

Precision machining, molding, and additive manufacturing

Precision machining gives tight tolerances for load‑bearing parts. Molding suits high volumes and consistent features. Additive manufacturing enables internal channels, lattices, and patient‑matched geometry.

Electronics integration

For active devices, map battery type, charging strategy, and sensor fidelity to clinical rate and life targets. Hermetic feedthroughs and sealed enclosures protect circuits and reduce irritation to skin and tissue near the implant.

Surface treatments, cleaning, and sterilization

Finishes and coatings control wear, friction, and protein adsorption. Choose EtO, gamma, e‑beam, or steam based on material compatibility and packaging to protect the body and surrounding tissue.

Validation, cleanroom assembly, and traceability

Plan IQ/OQ/PQ, SPC, and sampling to link critical features to gaging. Cleanroom flows, lot-level documentation, and serial traceability support audits and recall readiness. Use DFM/DFA to speed prototyping and scale-up services for volume production.

Challenges in Manufacturing Implantable Medical Devices

Every manufacturing decision — from material selection to sterilization — has a direct impact on patient safety and device longevity. The factors below show the technical and regulatory limits you must manage as you move from concept to production.

Biocompatibility and material interactions

Choose materials that limit tissue reaction and irritation to skin or deeper tissues. You’ll define test plans for cytotoxicity, sensitization, and long‑term degradation to prove safety.

Supplier controls and lot traceability reduce contamination risk. Validation of cleaning, sterilization, and endotoxin controls protects patients and supports audits.

Miniaturization, power, and thermal limits

Shrinking form factors for active implants forces trade-offs between battery life, telemetry range, and heat generation near the heart or other organs.

Design for low power, robust connectors, and fail‑safe modes to preserve function inside the body and improve reliability during long service life.

Human factors, regulation, and post-market duties

Human factors engineering refines alarms, user interfaces, and handling to reduce use errors and boost adherence for patients and clinicians.

The food drug administration expects PMA-grade evidence, V&V, cybersecurity for connected systems, and post-market surveillance like MDRs and CAPA.

Align development milestones with regulatory submissions, de-risk your supply chain, and maintain configuration control so your medical device meets expectations through its lifecycle.

Contact Fecision for Custom Medical Device Implants

Choosing a partner who knows regulatory pathways and clinical use helps you move faster from concept to clinic. Fecision offers services that link engineering, regulatory strategy, and manufacturing so your plans stay aligned with demand and patient needs.

Your partner for development, manufacturing, and quality services

We translate design inputs into manufacturable, compliant device solutions with integrated quality planning. Our team supports prototyping, verification and validation, and process qualification to shorten time-to-approval while keeping documentation audit-ready.

How we engage: from design inputs to production and lifecycle support

Our manufacturing covers precision components, electronics integration for active implants, and cleanroom assembly for products used in the body. We build quality in—from supplier qualification to sterilization and traceability—so your medical device is inspection-ready from day one.

We also offer lifecycle support: change control, post-market surveillance, and continuous improvement as field data and demand evolve. Whether you need an assist device subsystem, a complete assembly, or scale-up to volume, contact us to scope your program and stand up a plan that meets your goals.